prisonners at sea

archive > archive documents

Prisoners at sea’: stuck on board cargo ships, crews find their mental well-being under threat

They man the merchant ships that keep global trade flowing, but coronavirus restrictions mean thousands of seafarers are unable to return home. After months at sea, stress, fatigue and time away from loved ones is taking its toll.

Captain Bejoy Kannan, of Wallem Group. Photo: courtesy of Captain Bejoy Kannan

Kannan stood his ground and refused to let anyone on board while he contacted his ship’s management. This was a bold move. Chartering an oil tanker costs tens of thousands of dollars a day, so every hour lost eats into profits. Fortunately, the Wallem Group is one of the more supportive ship management firms and it negotiated that only eight men would come aboard, all wearing face masks and gloves, but “[the pilot] was touching things on the ship”, says Kannan.

“We were worried that if the gloves were infected, they might infect some of the equipment. We will only know in 10 days or more. We’ve been checking the crew’s temperatures daily.”

As the head of his household in India, Kannan feels unable to protect his elderly parents. His crew are also worried about their families and Kannan does his best to reassure them and keep up morale. He speaks in a calm, measured tone, but even so the strain is apparent – he has an infection in his left eye, perhaps the result of stress, and he has been speaking to the fleet’s psychologist.

Sailing to Singapore, Kannan plans to divert the ship to India to allow disembarkation of Indian nationals. If that is not permitted, “Very soon we are coming to the stage where we have to go on strike,” he says. “How long can we endure it? People want the cargo but what about the seafarers? Everyone talks of the doctors, the army and the police, but I don’t think people even know we exist.”

There are more than 50,000 merchant vessels in the world, including 5,150 container ships, each with an average crew of 22 persons – that makes for a workforce of well over one million people, responsible for delivering 90 per cent of the world’s goods stocking our shops. These men (and some women) are continuing to work seven days a week through the pandemic, their contracts extended because they are unable to disembark their ships.

“We all recognise the heroism of the health workers going the extra mile,” says Bjørn Højgaard, chief executive of Anglo-Eastern Univan Group, a Hong Kong-based firm that manages about 600 vessels. “But the coronavirus has also meant the normal turnover of seafarers is not taking place, or is in limited numbers.”

Seafarers’ contracts range from four to nine months, depending on their rank. A ship’s master (or captain) usually has a four-month contract while lower ranked seafarers can expect about eight months. Anglo-Eastern has around 15,000 seafarers at sea currently, and if travel restrictions continue, Højgaard estimates that 23 per cent of them will be working on extended contracts by the end of this month.

“We shouldn’t feel sorry for the seafarers, we should celebrate them, praise them for what they are doing,” says Højgaard. “They are proud of what they are doing, fulfilling a service to the world.”

Kannan (left) on board the China Dawn with a Brazilian pilot and a crew member on April 11. Photo: courtesy of Captain Bejoy Kannan

But extended contracts and the uncertainty surrounding coronavirus are placing increasing pressure on the mental health of crew members.

“In the long run, if people can’t get relief and go home, they will eventually burn out and be incapable of doing their jobs,” says Højgaard. “The longer this drags on without people being relieved, the more pressure will build up and, at some point, that pressure might boil over.”

There is an increasing awareness in the maritime industry of mental health. A study by Yale University, published last October, spoke to 1,572 seafarers of different ranks around the world and found that within the two weeks prior to being surveyed, 20 per cent had contemplated suicide or self-harm, 25 per cent had suffered depression and 17 per cent had experienced anxiety. Key factors were violence and bullying, a lack of job satisfaction and not feeling valued.

David Heindel, chairman of the ITF Seafarers’ Trust charity that commissioned the study, said in November: “The more we talk about mental health, the more we reduce the stigma associated with it. This report really helps us to understand the contributing factors and provides a basis for demanding some fundamental changes in the way the shipping industry operates.”

“Then coronavirus hits and what happens is that the stress level goes up – worry about getting infected, worry about family back home, worry about when they get into port will they be infected by people on shore,” says Frank Coles, chief executive of Wallem Group.

Captain Rajnish Shah. Photo: courtesy of Captain Rajnish Shah

Coles tells of a Chinese captain who wanted to disembark at a Chinese port and threatened to discharge his cargo if he couldn’t go home. That captain was eventually persuaded to do one more voyage. And another captain, concerned about his crew getting infected, refused to allow Singaporean officials to board.

“Crews are becoming more concerned and upset, afraid of being infected by what they see as the dirty side of being on shore,” says Coles.

Captain Rajnish Shah has stood up for his crew, demanding that their lives not be compromised for the sake of profit. When he boarded the bulk carrier Tomini Destiny on a four-month contract on August 28 last year the world was a very different place. An error surrounding his expected relief meant he and some crew members were not able to disembark in Switzerland and return home at the beginning of the year, but he took it in his stride.

“We thought it was a one-off thing,” says Shah. “We said we have to move on, we had an important Gulf of Aden transit coming up and had to take precautions against pirates in Somalia.”

He and his crew succeeded in avoiding the pirates, but there was more danger ahead. As the Tomini Destiny approached Chittagong port, in Bangladesh, Shah made plans with the ship’s owner for the cargo to be offloaded using trains, avoiding the need for dock workers. But when the ship reached port at the end of March those plans had come to nothing and 60 local workers demanded to come on board.

“Under the situation of the pandemic that was not acceptable because the exposure risk to the crew was huge,” says Shah. “Bangladesh had also gone into lockdown.”

Shah and his crew on board the Tomini Destiny. Photo: courtesy of Captain Rajnish Shah

A week-long stand-off ensued, during which the crew closed the hatches and rigged up razor wire to prevent access to the ship. Shah reached out to non-government organisation Human Rights at Sea, requesting better protection for his crew during cargo operations in port. His determination paid off and on April 6 the personal protective equipment (PPE) came through and the local workers used it while offloading the cargo.

The incident marked a critical point in the pandemic – a ship’s captain invoking Master’s authority (under the International Safety Management Code) in the interests of his crew, bringing him into direct conflict with the owners’ interests.

“I’m a master with 16 years’ experience and this is the first time I’ve ever had to exercise Master’s authority over owners to protect my crew,” says Shah. “The owners are in it for commercial interests, every day’s delay costs them. But the whole world is in turmoil. It’s unfortunate when the concerns of the crew are ignored for the sake of profit. Someone needs to stand up.”

The issue has now been brought to the attention of the Indian government through the Directorate General of Shipping, the Indian High Commission in Bangladesh, port authorities and unions.

We have seen a real lack of information, either under-reporting or negligence in reporting the issues. They just want to be told the truth, people can deal with the truth David Hammond, founder, Human Rights at Sea

David Hammond, founder of Human Rights at Sea, says the lack of access to good-quality PPE is a key issue.

“You rarely see masters taking such stands because they can get blacklisted. But masters are becoming more vocal and they come to organisations like ours to fight their corner. The master isn’t just protecting his crew, he’s protecting the global sea lanes,” says Hammond.

Human Rights at Sea has a number of WhatsApp groups it uses to keep in touch with seafarers of all ranks. Since March 22, there has been a surge in demand for PPE on these informal channels, as well as in queries about when they can sign off.

“We have seen a real lack of information, either under-reporting or negligence in reporting the issues,” says Hammond. “They just want to be told the truth, people can deal with the truth. A lot of the crew are saying, ‘We just want to know what is happening.’”

Kishore Rajvanshy is managing director of Hong Kong-based Fleet Management, which manages about 520 ships. Before taking a management role, he was a seafarer and served as chief engineer.

“What keeps me awake at night is worrying how long this will last,” says Rajvanshy. “For staff on board, one or two months [of extended contracts] is OK, but eventually there has to be a way to relieve people.”

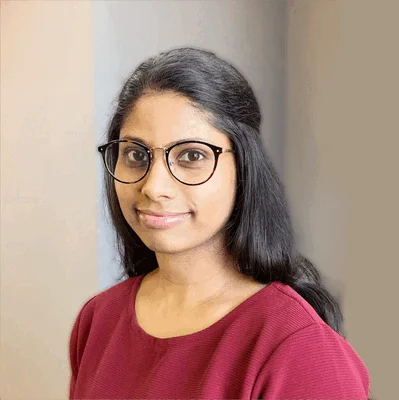

Mental health is still something that people neglect and that is stigmatised. It’s important that people on land understand the pressures and issues that seafarers face so they can be better supported Rini Mathew, clinical psychologist

Fleet Management is giving crew members who have their contracts extended a 25 per cent pay rise as well as an increased daily internet data allowance, so they can keep in contact with family.

Five months ago, the firm set up a dedicated division, Fleet Care, staffed by a team of eight and offering support to seafarers, from managing grievances to reaching out to family members to celebrate birthdays. On March 23, with the support of the charity Sailors’ Society, it launched a 24/7 helpline, Crisis Response Network, to offer confidential advice and support.

“We’ve already had quite a number of people use the helpline, about 25 people in one week,” says Captain Randhir Mahadik, the Mumbai-based head of Fleet Care. “Our ships are multilingual, so the support is available in Mandarin, Tagalog, many Indian languages and others.”

With an average of 22 men on each of the 520 ships, those 25 calls represent a fraction of the fleet’s staff, but also a turning point in addressing seafarers’ mental-health needs.

Rini Mathew, Fleet Care’s full-time clinical psychologist, says that when she tells her mental-health colleagues that she works with seafarers they are usually surprised and unaware of the specific challenges that they face working away from home.

Rini Mathew, a clinical psychologist. Photo: Fleet Care

“Mental health is still something that people neglect and that is stigmatised,” says Mathew, who is also based in Mumbai. “It’s important that people on land understand the pressures and issues that seafarers face so they can be better supported.”

She offers one-on-one counselling sessions for Fleet Management’s crews, but the logistics of remote therapy can be challenging. Confidentiality is the cornerstone of the therapeutic relationship, but seafarers often have to take the session by phone in a ship’s communal area, which means the captain must ask others to leave the space.

“And then there’s the challenge of the person on the vessel talking to a complete stranger who they can’t even see,” she says. “It takes time to build that relationship and trust. But often these people are reaching their threshold – they can’t take it any more, they need help.”

Problems can quickly escalate in the enclosed environment of a ship, so Mathew usually offers a session once every four days, rather than weekly, and follows up by sending psycho-education materials.

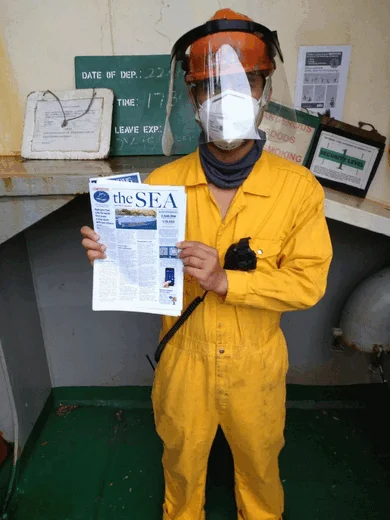

A member of the Mission to Seafarers delivers toiletries, snacks and a SIM card to a Myanmese seafarer aboard the KMTC Qingdao in Hong Kong on April 22. Photo: Mission to Seafarers

Most of her sea-bound clients experience depression or anxiety, sometimes a combination of the two, which is exacerbated by a sense of isolation and distance from home.

“When you are working at a stretch for so long it can lead to chronic fatigue syndrome. Once you start feeling that it often leads to other problems – not being very active or not being able to do duties well, which can lead to accidents,” she says.

The longer the pandemic goes on and contracts are extended, the more serious fatigue becomes. A typical shift pattern might be to work from 12am to 4am, have eight hours off, and then work from noon to 4pm. Doing so seven days a week for six to nine months takes a toll. Go beyond that and tensions mount.

The Mission to Seafarers is a Christian welfare charity serving merchant crews around the world. It has operated in Hong Kong since 1863 and offers a friendly ear to visiting seafarers as well as international legal advice and counselling.

Reverend Stephen Miller, the mission’s regional director for East Asia, says, “the Maritime Labour Convention exists because if you work shifts seven days a week for more than a year then you become fatigued, [suffer] sensory overload and your mind switches to something else. That’s when accidents happen – collisions at sea, accidents on board the ship, all these things happen when people are fatigued.”

This virus is a great opportunity for us to initiate change and put in procedures to call on in future, because it will happen again Tim Huxley, chairman, Mandarin Shipping

Coronavirus restrictions mean mission staff can no longer go aboard ships in Hong Kong, so instead they mask up and go as far as the gangplank at Kwai Chung container port to deliver newspapers, toiletries, snacks and entertainment such as pre-recorded football matches.

“It makes them feel more human if we can buy snacks from their home counties, India or the Philippines, anything that can give them a bit of comfort,” says Miller, whose mission is in touch with thousands of seafarers through Facebook and WhatsApp, and is trying to maintain calm.

“It’s a pretty lonely and isolated life for a seafarer, but they are even more isolated now. There’s only so much you can do before people start losing it.”

Tim Huxley, chairman of Hong Kong-based Mandarin Shipping, says seafarers have to be seen as essential workers and an accommodation must be made to allow them on and off ships. “This means we need to get various stakeholders in the business – the International Maritime Organisation, the United Nations body that oversees shipping; the flag states; immigration; and medical departments in their representative ports – to work together, which is going to be a groundbreaking move by the shipping industry.

“This virus is a great opportunity for us to initiate change and put in procedures to call on in future, because it will happen again. This experience will allow us to be better prepared next time.”

A seafarer on an OOCL ship with a shipping magazine he received from the Mission to Seafarers in Hong Kong on April 23. Photo: Mission to Seafarers

For Hammond, the solution is “ring-fenced global hub points” for the safe onload and offload of crew in order to keep global trade flowing.

“People need to understand that there are 1.4 million to 1.6 million people moving 90 per cent of the world’s goods,” says Hammond. “If they want that to continue, we need to support that workforce, which has an immense impact on all our lives.”

“People would not get on a plane if they thought the pilot never got off the plane,” says Wallem’s Coles. “But they are quite happy to let these [seafarers] sail around for months at a time.”

“If people want the shipping industry to survive, there should be an opportunity for us to get off and go home,” says Captain Kannan. “Don’t only think of commercial gain, spare a thought for us. We are tired and depressed and want to go home.”